Bollywood Masala Mix

a true trailblazer

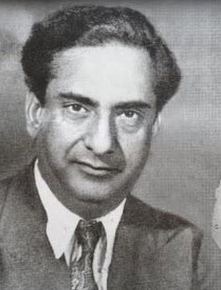

Amidst the tortuous and fleeting pathways of stardom in the galaxy of Indian film music, there is only one music composer whose name evokes unbridled love, respect, admiration and gratitude. To date, he is regarded as the ultimate mentor, a supreme composer, a trailblazer, an excellent teacher, a superb voice trainer, adviser, a mega talent hunter, and above all, a most beloved human being who cared deeply for the welfare of his singers, musicians and colleagues. This Polaris of film world is none other than Master Ghulam Haider. His career in films spanned a mere eighteen years from 1935 until 1953. He gave music to approximately thirty six films but his legacy is far-reaching that he shall always remain the North Star of film music.

Master Ghulam Haider’s legacy is everlasting. His knowledge of music was extensive, his ability to recognize vocal talent was extraordinary, his potential to mentor, nurture and groom the juvenile talents he discovered remains unsurpassed, his prophetic statements have come true even beyond his wildest imaginations, his service to fellow composers and the industry remains unforgettable, his treasury of non-film songs is as exquisite as his compendium of film songs, the reverence he commanded from his singers and musicians is unmatched, his revolutionary style of music opened a cosmos of melody, rhythm and fusion that rules the film music world even today. Master Ghulam Haider (MGH) remains the Master of masters of film music.

Master Ghulam Haider (MGH) revolutionized Hindi film music in more than one way. His mastery of classical music, extensive knowledge of Punjabi folk music and its sub-genres, combined with his sharp intellect made him concoct a fusion blend of film songs steeped in classical raaga based melodies and engulfed by folk rhythms. The result was magical giving rise to songs with long preludes, beautiful melodic segments interspersed with pulsating rhythmic overtones and interludes that were either tantalizing and fleeting or rich and grand to savor till the antara followed. The finished composition resembled a rich tapestry, tightly woven in many shades and colors depicting a scene or situation with amazing clarity, depth and structure. The orchestra of Master Ghulam Haider was renowned in Lahore and its timbre recognizable instantly. Thus, MGH songs carried a stamp of authenticity and originality.

This experiment of combining folk traditions with classical base for a three-minute film song had not been attempted before MGH introduced it in 1941 in the runaway blockbuster film “Khazanchi”. The thirties era was dominated by the New Theatre composers Boral, Mullick and Baran in Calcutta and the Bombay school dominated by Ustad Jhande Khan, Anil Biswas, Saraswati Devi and others. While these composers also experimented and introduced western orchestra into film songs, the classical and folk genres were kept distinct. MGH not only blended the two boldly but also combined it with the clarinet and the inimitable dholak and other percussion instruments to give film songs a joie-de vivre that was utterly irresistible and uplifting to the public who were mired in the freedom struggle and the second world war. This first successful fusion by MGH has formed the foundation of Hindi film music.

It is either serendipity or an uncanny ability to spot talent that MGH possessed in abundance. He used it many times and each of his discoveries turned out to be pure gold. Not only did he train, groom and mentor the three most versatile female singers of the sub-continent (Noor Jehan, Lata Mangeshkar and Shamshad Begum), he had supreme confidence in their abilities even when they were merely teenagers. The way he spotted talent and nurtured it until perfection reveals a kind-hearted composer who cared deeply for his singers and musicians. As revealed by Shamshad Begum to Gajendra Khanna, her talent was spotted by MGH at an audition for the Jenaphone Recording company. She sang many private songs and naats (more than a hundred perhaps) under this banner whose house composer was MGH. Unfortunately, most of these records are unavailable. The fusion style perfected by MGH started from the film Khazanchi and through its songs the public was introduced to the inimitable magic of Shamshad Begum.

Noor Jehan’s talent was spotted by MGH when she was brought to his studio as a versatile child artist. Upon hearing her, he recommended her to his friend Dalsukh Pancholi who signed Baby Noor Jehan for the Punjabi film Gul-bakavali in 1939. The elegant classical songs that she rendered in her strong, raw voice catapulted the singer, composer and producer to the top of the charts of Punjabi cinema.

The discovery of Lata Mangeshkar by MGH has several versions. One claims he spotted her at a music contest in Maharashtra in 1942 following the spectacular success of the blockbuster film Khaandaan. Another claims MGH noticed a frail girl on a train singing softly to herself. He used a stick and a plate to compose a melody on the train and asked the girl to sing. She sang it to perfection. He then improvised the song and found the girl could again render it perfectly. Amazed by her talent, he asked her to come for an audition the next day. It is said that Lata waited patiently all day outside his studio and was finally called for audition in the evening. MGH found her voice enchanting on mike and took her to Shashadhar Mukherjee. Spurned by him, MGH signed Lata for ‘Majboor’. The rest of the tale is history.

Another young talent spotted by MGH was a seven-year-old girl who appeared on stage at a wartime concert in Ferozepur in 1943. She sang a thumri and then a song based on raag Malkauns. After hearing the girl sing, MGH came on stage, patted the child on the back and made a prophesy that she would become a great singer one day. The words came true much after MGH’s demise on November 9, 1953. The child artist who won his heart in 1943 was Sudha Malhotra.

Other singers who were either introduced or nurtured by MGH in films include Umrao Zia who featured as an actor/singer in his first film, ‘Swarg ki Seedhi’ in 1935 and then became his Begum, Zeenat Begum (who sang a non-film version of a song from Khandaan in 1942 and then sang for Pandit Amarnath in Nishani (1942)), Surinder Kaur who was invited personally by MGH from Lahore after the partition and debuted in Hindi in his film ‘Shaheed’ in 1948, and the singer Munawwar Sultana (not to be confused with the actor Munawwar Sultana) who sang for him in Mehendi (1947) and Aabshar (1953). There is mention that MGH also liked Mohammed Rafi’s voice in Lahore and recommended him to become a student of Feroze Nizami.

The child prodigy Master Madan who died at the tender age of fourteen in 1942 was an extraordinary singer, famous all over the land and patronized by Maharajas to sing in their durbar. Only eight of his recordings have survived to date. Two of these eight songs are in Punjabi and were recorded in Lahore with the orchestral support of MGH.

This impressive list of talents was discovered by MGH in a short span of approximately ten years.

As a composer for the Jenaphone Record Company in Lahore, MGH had the opportunity to compose music for both films and non-film naats, ghazals and geet.

MGH spent time in Amritsar before settling down in Lahore around 1933. He absorbed the rare raags and taals used in Gurbani and befriended many famous singers of the town and enhanced his knowledge of music. Bhai Santa Singh is regarded as one-of-a-kind prodigy who could sing extremely high notes in perfect sur and slow taan for a very long period. He was the senior most singer of Gurbani at the Golden temple in the thirties. MGH persuaded Bhai Santa Singh to come to Lahore and record his renditions for posterity. Bhai Santa Singh obliged and MGH had the opportunity to give orchestral support in the form of preludes and interludes for Bhai’s kirtans. Eight of these have survived on four 78-RPM records.

After the partition, when most of his musicians expressed a desire to migrate to Lahore, MGH begged them to stay on in Bombay as they were at the top of the charts. However, the uncertain times and the prospect of establishing a film industry in a nascent nation held attraction for them. MGH did not merely plead with them to stay but even offered each of them two month’s salary as bonus to compensate for any losses they might incur by staying back in Bombay. It is only when this kind proposition was also not taken up, did he decide to migrate to Lahore while finishing assignments in Bombay. He cared deeply for his musicians and their families.

MGH left this world too soon at age 44 on Nov 9, 1953.

Based on the infamous 2012 gang-rape case involving 23 year-old survivor Jyoti Singh, “Delhi Crime” highlights the major cultural issues associated with violence toward women in India. Mehta states that during a separate film project in India, he came into contact with Neeraj Kumar, who was the former Commissioner of Delhi Police. It was Kumar that suggested to Mehta that he make a film on the 2012 case, which has captured the world’s attention.

In the mini series, Mehta exposes Delhi’s police force as being undertrained, underfunded and corrupt as officers became the focus of activist groups immediately after the incident occurred. Mehta also portrays the daily problems that fall out of police officers’ control. He stated in an interview with The Guardian that officers “don’t get to see their families for weeks at a time during an investigation” and that officers lack the access to vehicles necessary to travel to the crime scene.

Mehta acknowledges the limits to the factual basis of the story by bringing this story to the mainstream audience and stating that “tiny details” of the crime scene were altered for dramatic effect.

By partnering with a platform as wide-reaching as Netflix, the film has the potential to educate the Indian community as well as the broader global community on the danger and injustice women face in India.

One real character depicted in the series is Vartika Chaturvedi, a deputy police officer. Chaturvedi is tasked with overseeing the investigation into the Jyoti gang-rape case. Chaturvedi’s daughter is shown to experience sexual harassment in multiple public settings, which she tries to bring to her parents’ attention.

As a young woman who is looking to leave India for Canada, Chandini Chaturvedi expresses her anger over the fact that she is unable to execute normal tasks such as taking the metro without fear. This depiction of India’s public settings is a theme throughout the mini series that paints a disturbing reality seen in India.

This is not the first time Jyoti Singh’s case has been covered in the global media. In 2015, the BBC released a documentary called, “India’s Daughter.” This film, released on International Women’s Day, dives into Jyoti Singh’s case through a series of interviews with convicted rapist Mukesh Singh, who made misogynistic remarks defending the 2012 gang-rape. At one point he said, “A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy.”

British documentary maker Leslee Udwin described the recent surge of films and overall media attention from the western world surrounding India’s sexual assault problem as the “Arab spring for gender equality.”

I first discovered Indian films: Russell

"The Mask" director Chuck Russell always wanted to be a part of Hindi films as he loves the way Bollywood movies incorporate song-and-dance routines. Russell, who has finally directed a Hindi film with "Junglee", said both the industries are good at telling larger-than-life stories.

"I was jealous of Indian directors when I first discovered Indian films. As a teenager, I found you guys do song and dance in every or any genre. In the West, the musicals were very limited. There are many differences but we (both) can tell larger-than-life stories and our stars can carry it," Russell said.

The 60-year-old director is not completely alien to the new Bollywood, having watched "3 Idiots", "Sultan", "Baahubali", "Raazi" and "Bareilly Ki Barfi".

"When I see the world, I want to try to incorporate stories from different cultures. Also, I had realised that if everyone can enjoy a film like 'The Mask', we are similar in a way when it comes to consuming entertainment," he said.

"My mother loved India very much, she passed away just as we started work on the 'Junglee'. She was a travel agent. I am carrying on the tradition of my family," Russell added.

Another reason for the director to board the project, led by Vidyut Jammwal, was the Indian setting, which best suited the family entertainer. "(I felt) It should not be told with western actors. This is about the relationship between a man and an elephant and it is in the Indian DNA for centuries. I was comfortable with it being an Indian story.

"At first, I did not know why they approached me for this film but I realised it was because I am always dealing with the human and animal relationship angle in my films."

Whether it was "The Mask" with Jim Carrey or "The Scorpion King", starring Dwayne Johnson in his acting debut, Russell said he always develops stories around his actors.