June 21, 2017 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

Bernard Heydorn

Canada celebrated its 150th birthday on July 1 of this year. Its reputation stands high as the most reputable country in the world according to a report by the Reputation Institute. The ranking was reportedly based on quality of life, quality of institutions, and level of economic development. In the last six years, we have never ranked lower than second place.

Canada has also been ranked most desirable country to live in. Also the most admired country with the best reputation in the world (2015). Added to all of this, Canada was ranked the most well respected country in the

world by holiday makers (2015). We were ranked second best country in the world in March 2017, edged out by Switzerland. It is interesting to note that the U.S.A. dropped to the rank of #38 in the list of the world’s most reputable countries (2017).

Even though not born in Canada, I feel blessed to be living here. I have adjusted to life in Canada in spite of the harsh winters. We take our security, high level of tolerance, freedoms, multiculturalism, peace and a just society, for granted. Changes may however be coming for we live in a global village and we have to take stock of what is happening around us.

As it stands now, we are being threatened by an axis of evil, namely Putin’s Russia, Trump’s America, North Korea, and China. Be it climate change, nuclear war, racism, intolerance, protectionism, cyber warfare, extremism, radicalization, and demagoguery, our democratic institutions and peace are at stake.

Added to that, there is already “a Fifth Column” within our own borders who may be doing their best to stir the pot. What they are cooking up is a recipe of racism, extremism, and even radicalization. This group has been inspired and encouraged by Trump’s vision for America which they would like to import into Canada. Estimated at being about 20% of the Canadian population at present, they include both Canadian borned and immigrants. A few current and aspiring Canadian politicians seem to be infected by this political disease. Their ability to capitalize on the Trump mania and the destabilization of our democracy cannot be ignored.

When I was growing up in British Guiana, the fear was of “communism”. This lead to massive, political upheaval and mass exodus. Around the time that I was born, during the Second World War, the axis of evil could have been described as Germany, Russia, and Japan. History just seems to repeat itself.

I was a new resident of Canada when it celebrated its hundredth birthday in 1967. The event was marked by Expo 67 in Montreal which was a great success. It helped to put Canada on the world map. We have had different Liberal and Conservative governments before and since, all succeeding in preserving the rule of law and a stable and healthy country.

Canadians have been viewed by some as being “boring’ people. The fact that we don’t have regular riots on our streets doesn’t make us boring. We are perhaps not as “flamboyant” as our neighbours to the south but that is okay. We have a tradition for being peace keepers around the world. We would like to keep it that way. We are locked in by long winters and we do “hibernate”. We enjoy the quiet life.

One of the best feelings I have, having traveled abroad, is to cross the border and return to Canada. It is a special feeling of coming home, of breathing a sigh of relief, in spite of how well the holidays and travels may have been. To return to the safety and security of your home country is something I wish for my children and grandchildren. In fact I wish it for all people. Let us celebrate our country and strive to maintain its heritage over the next hundred years and beyond. If the creeks don’t rise and the sun still shines I’ll be talking to you.

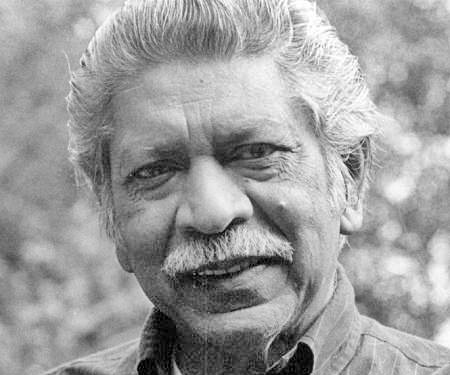

By Romeo Kaseram

Ismith Khan was born March 16, 1925, at 48 Frederick Street, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, the one son of five children to Faiez and Zinab Khan. Both parents were Pathans, as was his grandfather, Kale Khan. It was the grandfather who figured prominently in Khan’s early life, influencing the young man with his Pathan military past, his Indian nationalism, and his anti-colonialism views. In Trinidad the grandfather was respected in the Muslim community as a militant community leader, having been shot and wounded on the leg by the colonial authorities during the Hosay Riots in south Trinidad in 1884. Kale Khan remained a central, patriarchal figure in Khan’s early life. In a time and place where the majority of those around were descendants of indentured labourers, the grandfather proudly retained the distinction of having arrived in the Caribbean as an immigrant and a free man. The family first came to British Guiana from India; then moved 15 years later to Princess Town in south Trinidad, and afterwards to the capital city of Port-of-Spain, where Khan was born.

Khan grew up with his grandfather telling him stories about his militancy in northern India. In private correspondence to Arthur Drayton in 1983, Khan says of his grandfather, “[During] one of the uprisings [in India], when Indians were called upon to shoot Indians, he fired at the British, chucked the military, and took off with his family… My grandfather was ever involved in all things anti-British… his was rebelliousness, his life was one of dissent, he ridiculed the Raj, [and] chastised fellow Indians for being run over roughshod by the Sahibs”.

Despite being Muslim, the young Khan first attended an elementary Anglican Church school, and later entered what was then the elitist Queen’s Royal College. He later worked as a reporter at the Trinidad Guardian, where he met Sam Selvon. While Selvon headed to the UK in what would later be called the Windrush Generation, Khan left Trinidad in the 1950s for the US. There he acquired a bachelor’s degree in sociology from the New School for Social Research in New York, and later a master’s degree in creative writing from Johns Hopkins University. He settled in the US, living in Manhattan between the years 1955-1970; in this time, he worked as a research assistant at Cornell University, and was an instructor in creative writing at the New School for Social Research between the years 1956-1969. In 1970 he moved to Southern California as a visiting professor at Berkeley from 1970-1971. He taught Caribbean and comparative literature at the University of California in San Diego from 1971-1974, and at the University of Southern California in 1977; from 1978-1981 he taught at California State College in Long Beach. He moved back to New York in 1982, and was an adjunct lecturer at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn.

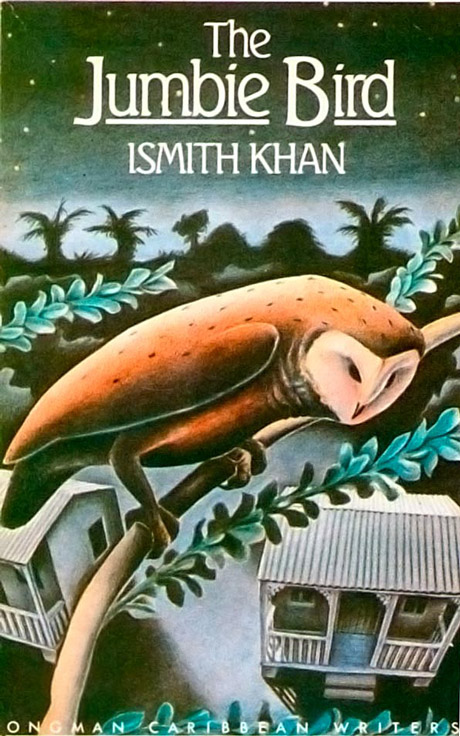

Khan published three novels in his lifetime: The Jumbie Bird (1961); The Obeah Man (1964); and The Crucifixion (1987). He also published a book of short stories, A Day in the Country and Other Stories (1994). His well-known work is The Jumbie Bird, which as Drayton writes in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English, “uses family history as a point of departure to examine the Trinidad-Indian predicament. Trinidad’s only novel with extended treatment of this subject, The Jumbie Bird, draws on history to explore the ambivalences of British officialdom and the consequent confusion among the migrant population. Khan presents, through three generations, syndromes of exploitation, bewilderment and misery, of wavering transition, and of problematic but possible integration”. Writing in Caribbean Beat, James Ferguson also cites the semi-biographical linkages, and notes how the novel “explores the social, political and ethnic tensions prevalent at that time through the lives of an Indo-Trinidadian family of three generations… But this is no ordinary family, for the dominant figure is Kale Khan, an aging patriarch and grandfather to the novel’s main character, the adolescent Jamini. A formidable figure, Kale Khan is a Pathan…”

James notes the underlying theme in the novel to be “the conflict between the patriarch’s indomitable sense of his own Pathan identity and the process of acculturation that has shaped both his son and grandson. For while Kale Khan dreams of a return to his homeland, his son, Rahim, brought up in Trinidad, knows no other reality and feels no ancestral link with his father’s birthplace. Instead, he experiences the painful rootlessness felt by many second-generation migrants, made worse by fears of bankruptcy and poverty. ‘What goin’ to happen to us?’ he asks. ‘We ain’t belong to England, we ain’t belong to Hindustan, we ain’t belong to Trinidad.’ Rahim, in turn, has a son, Jamini, and it is largely through his eyes that we witness the growing conflict between the old and the new, the dream of return and the reality of staying.”

Similar themes of rootlessness, the incongruities within in-between worlds, and stark indigence emerge in Khan’s other writings, among them his short stories. In ‘The Red Ball’, the young protagonist senses the presence of the hegemony and authority that is the panopticon, colonial gaze as he sits in the water fountain in Woodford Square, Port-of-Spain: “[When] no one was going past he waded across the waist-high water to the green and mossy man-sized busts where there was a giant of a man standing lordly among four half-fish half-women creatures, a tall trident in his massive arm pointing to the shell of blue sky. He had touched the strong green veins running down the calves of the man's legs with fear, half expecting the severe lips to smile, or even curl in anger at him, but the lips stood still in their severity.”

This young man is also on the edge of actualising the gift he holds as a promising cricketer: “He turned and his feet slapped at the turf moving him along like a feather; his long thin body arched like a bow, the ball swung high in the air, his wrist turned in, and he delivered the shooting red ball that turned pink as it raced to the batsman. The batsman swiped blindly and missed, his head swung back quickly to see how the ball could have gone past him so fast. ‘Aye, aye, aye,’ the wicket-keeper cried out, as the ball smacked into his hands making them red hot.” It is in spaces as these where Khan’s writing excels for its exploration of the in-between worlds, where colonial domination impacts to create the agonies of futility, poverty, and rootlessness among the dominated.

Khan died in Brooklyn on April 24, 2002.

Sources for this exploration: Routledge Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English, Second Edition; ‘The Jumbie Bird: From East to West Indian’ – Caribbean Beat Magazine: http://caribbean-beat.com/issue-44/east-west-indian#ixzz4lKKPL2p5; and Fifty Caribbean Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook, Daryl Cumber Dance (ed).