August 2, 2017 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

Kamil Ali

The hundred-year-old home had two floors with an attic and a back porch.

Twelve-year-old Milicent Marnet’s widowed mom expressed excited interest to the real estate agent, who led them on a tour of the home.

A deep coal mine collapse had buried Milicent’s dad a year before. The authorities never recovered his body.

Milicent glanced out of the window in every room at the neighborhood, situated a

They now had the chance to move out of their tiny row-house unit in a dilapidated and overcrowded building, where the country’s economic depression had forced them to survive on pennies a day. Milicent’s parents had struggled to eke out a living on her dad’s meager income. They lived in a shabby coal mining village, where black dust from the coal factories covered all surfaces and coated the inside of every lung, working overtime to suck enough oxygen into failing bodies. The rural community’s life expectancy hovered around the mid to late thirties.

In her haste to grab the deal on the house, Milicent’s mom never asked the reason for the high frequency of ownership and several price reductions that made the property a bargain. She never questioned why the locals never showed any interest in purchasing the home.

She paid cash from her husband’s life insurance benefits to close the sale without the benefit of a lawyer. They moved into the residence two weeks later with brand new furniture, clothing, and appliances.

Milicent looked forward to spending the second half of her summer vacation experiencing suburban living.

On the first night, a bang on the ceiling above her room frightened her awake. She pulled the covers up to her chin and listened, not daring to move. She glanced around the moonlit room through slits between her eyelids.

Another bump in the middle of the night sent her scampering into her mom’s bed. Without a word, Milicent’s mom hugged her as she had done when they shared a bed after the death of the family’s patriarch.

“I had a nightmare.” She pressed herself against her mom.

“It’s okay, honey.” Her mom combed her fingers through Milicent’s hair. “You can sleep with me until you’re ready to go back to your own bed.”

“Thanks, Mom.” Milicent did not want to alarm her mom by disclosing her terrifying experience. Her mom’s comforting touch soothed her away into slumber.

They spent their first-day cleaning and setting up their new home. The full day of activities pushed the previous night’s ordeal from Milicent’s mind.

At nightfall, the traumatic memories of the night before returned when Milicent prepared for bed. She forced herself to confront her fears and sleep in her own bed. The alarm clock displayed ten thirty. Exhausted from the full day of work, she dropped on the bed and fell asleep almost immediately.

A loud bang stopped her heart and made her spring up in bed. She froze, only moving her eyes to survey her surroundings.

She clutched her throat and gasped from objects tumbling around in the attic above her. The rolling noise moved to her closet and dropped through a ceiling door to the floor inside the closet. The closet’s sliding door rattled. The clock showed the midnight hour.

Milicent hopped off the bed and darted out of the room. She dived under the covers of her mother’s bed, shivering from a cold sweat. Her mom wrapped an arm around her and kissed the wet hair at the back of Milicent’s head.

Sunlight chased away the creepy shadows of night and chirping birds replaced nighttime disturbances.

Milicent and her mom used local transportation to visit the city. They borrowed books from the library, shopped for clothing and bought groceries.

Upon their return home, her mom went to the kitchen to cook. Milicent reclined on a lounging chair on the back porch and read a book from the library. The sounds of summer gave her peace and contentment.

Nightfall brought renewed anxiety to Milicent. She had not disclosed the unnerving occurrences to her mom but asked her mom to sleep with her on the third night to get her accustomed to her own bed. They said a prayer for her dad before she hugged her mom and fell asleep.

A thud under the bed snatched her out of sleep. The clock showed the witching hour. Violent shaking of the bed made her mom sit bolt upright and grab Milicent to protect her.

“Get out of here!” A loud voice commanded. “Go back to hell where you belong!”

“Run Milicent!” Her mom screamed and jumped off the bed. Together they sprinted down the stairs and darted out of the house. They raced across the street. The lights in the home flickered on and off. The commotion inside bounced furniture around and shattered windows.

Half an hour later, an earsplitting screech and sudden silence filled the night air. The lights stayed on and they ventured back in to find the entire house in disarray.

Milicent and her mom researched the home the next day at the library. The first owner of the home practised witchcraft. Anyone who crossed her path suffered great tragedy.

Angry citizens formed a posse and marched to her house to burn her at the stake. She went into the attic and hanged herself with a vow to seek revenge by protecting her home from invaders. She died with no heirs.

The city took possession of the house and tried to sell it each time it became vacant. Many people died in the house and others fled the premises for their lives.

Milicent and her mother glanced at each other. They did not speak but knew each other’s thoughts. The stern voice in the house belonged to Milicent’s dad. He had returned from the grave to protect his family.

stream of writing

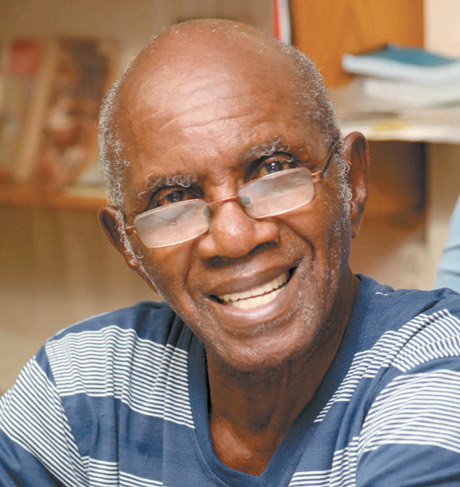

By Romeo Kaseram

Michael Anthony was born in the Mayaro, Trinidad, on 10 February 1930. His parents were Nathaniel Anthony and Eva Jones Lazarus. When Anthony was ten years old, his father passed away after a long illness. The next year, in 1941, the young man left Mayaro for what is now the southern city of San Fernando, where he spent a year, this experience being the basis for what would later become one of his better known novels, The Year in San Fernando (1965). Anthony’s early elementary education took place at the Mayaro Roman Catholic School. Following this, in 1944 he attended the Junior Technical College as a trainee mechanic in San Fernando after winning a bursary, this opening the door for him to join the Pointe-à-Pierre oil refinery, where he worked as a molder in the foundry for five years. Nurturing ambitions to become a journalist, Anthony endured employment at the foundry, even as he projected his creativity onto athletics while at the Pointe-à-Pierre operations. Some of his early poetry were published in the Trinidad Guardian in 1954, but this incipient prominence was inadequate to sustain his deeper longing for the writing life.

Anthony decided to further his writing career in the UK. Speaking to Richard Charan in the Trinidad Express in 2014, Anthony recalled his dream to write and publish the “short story”. Charan writes: “It was in 1953 that his friend Canute Thomas… got a scholarship from the company (then Trinidad Leaseholders Limited) to go to London. Anthony recalled: ‘As soon as he got to England, he wrote me saying: ‘Why don't you try to come up here? You are always talking of wanting to be a writer. This is the place to come. Publishers all around. Why don't you try and come?’ The next year, Anthony, following his dreams, was on a steamship bound for England.” Having arrived in 1954, Anthony settled in, found employment in factories, the railway, and as a telegraphist, while reaching out to the literary world. He contacted the Overseas Section of the BBC, which at that time was hosting a programme of verse and prose that was broadcast to the Caribbean.

Charan writes: [The BBC] were just changing their programme producer. The new one was coming from famed Oxford University. His name was Vidia Naipaul, a literary legend who belonged to Trinidad for the first 18 years of his life and is now regarded as one of the finest living writers. Anthony recalled sending Naipaul a short story and two poems for his consideration.” As Anthony recalls, “[Naipaul] sent for me and he said, ‘Mr Anthony, your short story has possibilities, but promise me you will not write another poem.’”

Anthony left the UK in 1968 for Brazil, where he worked as a cultural officer with the Trinidad and Tobago Embassy. He returned to Trinidad in 1970 with his wife, Yvette Phillip. Back in Trinidad, Anthony worked as a journalist and as a cultural officer in the Education Ministry with the Trinidad and Tobago government.

Anthony’s writings make up six novels, numerous short stories, along with historical writings, and as he has indicated, these draw substantially from his personal experiences. Among his works are: The Year in San Fernando (1965); Green Days by the River (1967); The Games Were Coming (1968); Streets of Conflict (1976); All That Glitters (1981); Bright Road to El Dorado (1982); The Becket Factor (1990); In the Heat of the Day (1996); Glimpses of Trinidad and Tobago, With a Glance at the West Indies (1974); Profile Trinidad: A Historical Survey from the Discovery to 1900 (1975); The Making of Port-of-Spain 1757-1939 (1978); First In Trinidad (1985); Heroes of the People of Trinidad and Tobago (1986); The History of Aviation in Trinidad and Tobago 1913-1962 (1987); A Better and Brighter Day (1987); Towns and Villages of Trinidad and Tobago (1988); Parade of the Carnivals of Trinidad 1839-1989 (1989); The Golden Quest: The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1992); Historical Dictionary of Trinidad and Tobago (1997); and, Anaparima: The History of San Fernando and Its Environment (2001).

Writing in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English, Arthur D. Drayton, notes Anthony’s body of work falls into two phases, the first “embracing his major fiction, effectively ends with Streets of Conflict (1976), though All That Glitters (1981) also belongs to it”. He adds: “Characterised by disguised eclectic autobiography, these works focus the developing consciousness of young protagonists, setting them in the landscape, society and ethos of rural Trinidad of the 1930s and 1940s. They offer period portraits that help reconstruct the neglected past, such as that of the selfless elementary schoolteachers so fundamental to the flowering of the country's first crop of intellectuals (projected through the motif of the portrait of the writer as a schoolboy) and the society's emerging ethnic pluriverse.”

In what is Anthony’s second writing phase, Drayton notes it begins, “with Profile Trinidad: A Historical Survey from the Discovery to 1900 (1975)”, and is made up “mainly of historical and cultural writings”. He adds: “Its range includes a re-focused history of country, city, towns and villages, the reclamation of the land's unsung heroes, and a chronicle of carnival. Later works in this area are his Historical Dictionary of Trinidad and Tobago (1997) and Anaparima: The History of San Fernando and Its Environment (2001).”

Drayton adds of both phases: “This enables the fiction to anticipate the later historical-cultural writings in engendering a potential for elevating national consciousness and pride; the integration of vernacular usages reinforces this. Being essential elements of the decolonisation process, antecedent to and characteristic of the early stages of post-colonial experience, these features establish for Anthony a place in anti-colonial discourse.” However, other critics tend to dismiss “his work as insignificant”, and disagree on Anthony’s depth, citing what Daryl Cumber Dance describes in Fifty Caribbean Writers, as an “apparent lack of concern with the major racial, socio-logical, political, and economic issues that engage many Caribbean writers”. Among the least caustic of these critics is Edward Baugh, who Dance quotes as saying: “If one says that [Anthony’s] best work has the clarity and luminosity of a shallow stream, this is not to disparage it but only to define its limitations and the nature of its appeal. Anthony attempts nothing grand, and is hardly concerned with ‘messages’.”

Anthony has twice been a resident member of the international writing programme at the University of Iowa in the US. In Trinidad and Tobago, he was honoured in 1979 with the Hummingbird Gold Award; and in 1988 he received the City of Port-of-Spain Award for contributions to history and literature. He lives in Trinidad with wife, Yvette, together raising four children.

Sources for this exploration: Richard Charan – Trinidad Express, January 26, 2014; Routledge Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English, Second Edition; Daryl Cumber Dance (ed.), Fifty Caribbean Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook.