May 4, 2011 issue

Arts & Entertainment

No back door when my water

flowed from Guyana

On Saturday June 29, 1963, I boarded the M.V. Ripon at John Fernandes Wharf on Water Street in Georgetown, British Guiana, bound for Barbados. Clutching all my worldly possessions, locked in a little suitcase, it was goodbye to my homeland, goodbye fuh good.

Having resigned my position as a teacher at St. Joseph's High School in Guyana at the end of that school year, I was fleeing the strife, strikes, trouble and violence that were tearing the country apart. These were the

dark days leading up to Independence in 1966. Even darker days were to follow.

I was journeying to join my parents and other members of my family who had emigrated to the island of Barbados the previous year. The exodus from Guyana had started in earnest after the Black Friday riots of February 16, 1962. Another Black Friday was to follow on April 5, 1963 when union workers who had been running a go-slow were locked out and threatened with dismissal. They were dispersed with tear gas and rioting ensued.

The strike movement picked up momentum with civil servants and the teachers' unions joining in until on April 18, 1963, a countrywide general strike started which went on for 80 days – a strike that was reported to be the longest general strike in history.

This was the backdrop to my departure from Guyana on the M.V. Ripon. An older brother of mine was with me as we joined about 75 other passengers and crew on the small, heavily laden motor vessel. The Ripon was just about the only means of getting out of the country at that time with everything on shut down.

We were both sad and glad at leaving. The long bread lines, the lack of fuel, food and other necessities of life, the political tensions, the racial violence, the country seemed to be disintegrating.

My brother had bought a ticket for a "cabin" so he could travel in relative comfort. I could only afford a ticket for a deck passage which I believe was about $25.00, my brother paying double that amount for his "cabin".

I had little sleep the night before the journey. This was enhanced by the fact that someone in our flat had left the water tap running in the bath which overflowed in the middle of the night and drenched the folks living in the flat below us as they slept!

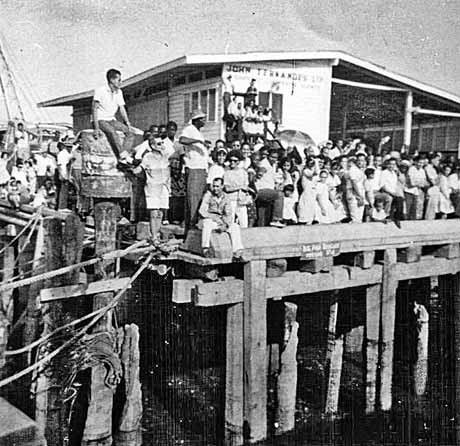

A crowd of well-wishers, relatives, friends and curiosity seekers had gathered at the dock. They included two of my uncles, a brother, close school friends, work associates and others. They pressed forward on the wharf to get a vantage point or climbed to get a better view. My heart was heavy. It was past 4:00 pm in the afternoon and the sun was starting to dip. The Ripon waited for high tide to depart, to avoid the sandbanks in the Demerara River.

You can see in the accompanying picture the departure as the ropes were cast off. I tried to smile and put on a brave face. The vessel sat low in the water, too low for comfort. More than fully loaded with over 70 passengers and their belongings plus the crew and cargo bound for Barbados, the water was already lapping high along the gunwales (sides). I remembered my father's words, "Water got no back door!" On top of that, I could not swim a stroke.

The vessel headed slowly up to the mouth of the Demerara River, past the red and white striped lighthouse, sentinel of the shores, past the jetty where I used to stroll to get fresh air and feel the tug of the Atlantic, out into the open sea.

The passengers huddled together on the deck, watching their homeland slowly disappear below the horizon. I recognized quite a number of my fellow travelers – folks of all races, ages and classes; families, babies and young children, businessmen, the Jesuit principal of St. Stanislaus College, a school that I had attended. Some of these folks from the "upper class" would not have "pissed" on me if they passed me on the street in class-conscious Guyana. Now we were all in the same boat, together (literally) – politics can be a leveler in more ways than one.

Soon we went past the shipwrecked Key Holt, sad sentinel to the port of Georgetown from the war days of the Second World War. For the first time I saw the ship up close, its sloping deck washed with creamy foam and waves, incessantly pounding it to bits, fighting for survival, fighting to stay above water, as many Guyanese were doing at that time and to this day.

By then, things started to get rough. Passengers in increasing numbers were rushing to the sides of the deck to "puke", looking ghastly green. The smiles and tears of farewell were being replaced with fear, nausea and anxiety. Those who had paid for a cabin like my brother, rushed down below. The Ripon's propeller started to bite the air making a chilling whine as the swells got deeper. The spray washed the deck.

It was almost sunset and the evening clouds were pulled down over the horizon, hurriedly closing this chapter of my life. Little did I realize that I would never see again many of the folks that I had left behind. The town of Georgetown, being below sea level, disappeared fast. The last I saw were the tops of tall palms dotting the East Coast, like feathers waving in the breeze and soon they too were gone. We were now left to the mercy of Tiberius in a wide open sea.

I went below to check on my brother in his "cabin". He was in a lower bunk in an open area not far from the engine room. The stuffy air, the pungent smell of diesel fuel, the vomit on the floor, the cries of children and sick people were ghastly. I tried to get my brother to come up on deck to get some fresh air but he could not even sit up.

As I ministered to him, someone shouted from the bunk above "Watch you head!" and proceeded to vomit from the top bunk. I had to leave him and rush back up to the open deck. My brother did not walk again for the next 40 hours, not until the sailors shouted "Land Ahead!" as we approached the far shores of the island of Barbados on the Monday morning.

On deck, the spray was now constant, the course set, the night clear with a canopy of stars. I made my way to the little cabin where dinner was supposed to be served, thinking that a little food in my "craw", might not be a bad idea to stave off seasickness.

There the table was set for three! I asked the cook where all the passengers were going to eat? He said simply that that was more than enough room for who would come to eat. He was dead right for the only other passenger to join me for dinner was a Jesuit priest, an Englishman, and my former principal from St, Stanislaus College. We made small talk as we ate. Suffice to say that I was not particularly a fan of this gentleman.

The cook then proceeded to tell us a tale of a sister ship to the Ripon, the M.V. Zipper, a converted mine sweeper from the Second World War, which had sunk on this same voyage to Barbados the year before with total loss. Some wealthy Guyanese reportedly lost their fortunes when that ship sank.

All of this talk of sinking left me with a sinking feeling. I went back on deck. I was alone except for the occasional crew member and a life boat. I decided to climb into the life boat to spend the night. That way I would be protected from the spray and would have a space reserved, in case the Ripon decided to dive into the deep.

I pulled the tarpaulin of the lifeboat over me and settled down in the boat. It was a beautiful night although the beauty of the night was lost on me. I started to pray for myself and all the sick people on board. I wondered if we were going to make it. I was only 18 years old, and already a refugee. We were perhaps the first "boat people" as we fled Guyana in 1963.

Soon I had company – first a rat who was also in the life boat, scurrying around my feet, trying to get up close and personal. Not feeling particularly hospitable I managed to evict it.

Then it was the Captain making his final rounds for the night who stumbled on to me in the lifeboat. At first he thought that I was a stowaway. I quickly found my ticket and showed him. I then asked him if it was always this rough, to which he replied it was the calmest trip of the year so far. He then bade me goodnight and went on his way. I couldn't imagine what the roughest trip would be like.

I hooked my leg into a side railing just to make sure I didn't get tossed overboard in my sleep, and dozed off. It was a fitful sleep but no seasickness. Sunday morning broke out bright and beautiful. The crew were all upbeat – the passengers nowhere to be seen. I went for my three strapping meals that day with none but the cook or another crew member to converse with. I had got accustomed to the motion of the ocean. The colour of the water had started to change to a lighter colour.

Sunday gave way to night time and another restless night. On Monday morning the colour of the water had definitely changed. From muddy or grey it was now blue green. Then I saw a sight to behold: little silver fish jumping in and out of the water in schools, seemingly flying through space. The sailors said that they were called "flying fish".

Soon a cry rang out from one of the sailors, "Land Ahead!". My heart jumped into my mouth. "It's Barbados!" I looked but could only see a hazy line on the horizon. Then there erupted a commotion from below deck. The passengers were coming up from their cabins like rats flushed out of a hole.

They were walking, talking, smiling, joking, pointing excitedly at the little cloud on the horizon that the sailors called Barbados. They all, including my brother seemed to have made miraculously quick recoveries from their illnesses. The boat was rocking and rolling but it did not seem to bother them one bit.

In about three hours, by noon on Monday, we were close to the shores of Barbados in Carlisle Bay outside of Bridgetown. There, the beautiful sight of peace and quiet, no tear gas, no rioting, no army, just people walking about normally and conducting their daily business.

A semi-circle of pastel houses, set in a cotton wool sky, a flotilla of fishing boats, blue green bay, inter-island schooners, freighters, and large tourist liners could be seen. It was on this very bay, years later, that I took my wife-to-be on our first date. It was under those palms we had our first kiss.

My mother jumped into my arms when she saw me. My father, brothers and sisters looked relieved. My brother, the fellow passenger still looking wobbly, said two words - "Never again!" True to his word, he never traveled on an ocean going vessel again in his life.

A great Aunt of mine also made a trip from Guyana on the Ripon when she was in her 80's and was so sick, on arrival in Barbados she said, "Put me down here fuh dead!".

It was Monday, July 1, 1963. Ironically, the General Strike in Guyana ended one week later on July 7, 1963. Guyana would suffer many more tragedies and much more trauma. I would move on to an uncertain future. Many Guyanese would flee Guyana in many different ways. Some have told their stories. Many have tales to tell. This is my tale. It's almost 50 years but it seems like yesterday. Whatever happened to the Ripon, I do not know. If the creeks don't rise and the sun still shines, I'll be talking to you.