Book Review

inspired narrative

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

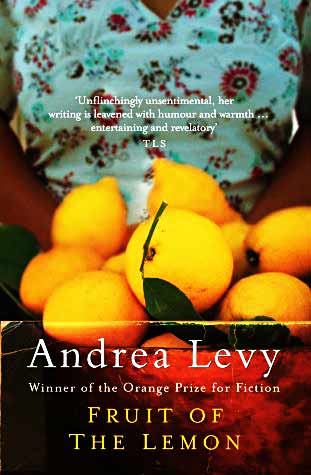

Andrea Levy's third novel Fruit of the Lemon devotes itself as much to the topic of black Jamaican immigrants in England, especially the children of such immigrants, as her earlier novels Every Light in the House Burnin' (1994) and Never Far From Nowhere (1996); but Faith Columbine Jackson, narrator of Fruit, in addition to reflecting on her experience in England, also describes a visit to Jamaica where she becomes immersed in hugely self-revealing cultural exploration. For, like her heroine, Levy herself was born in England of Jamaican parents who had arrived by the "MV Empire Windrush" in 1948, an historic voyage that brought the first boatload of Jamaicans to herald a migration of tens of thousands other West Indians to England in the 1950s.

Although Fruit is divided into three parts, Part Three consists of no more than half a page briefly noting the narrator's return from Jamaica to London on 5th November, Guy Fawkes Day, the very day on which her parents arrived in England, in 1948. Since half of her narrative considers her growing up and working in London in Part One, and the other half - Part Two - retails her mind-blowing sojourn to her ancestral homeland, Faith's return to England in Part Three merely supplies a convenient, circular if perfunctory conclusion to the novel.

Faith's growing up and working as a dresser of television actors in London follows the pattern in Levy's first two novels exposing attitudes inspired by racial prejudice against black immigrants in England in the late 1970s. Race and colour appear almost as a prescribed agenda. Even if Faith mixes freely with white friends as roommates, race and colour always appear, either when she applies for a job or observes a blatantly racial incident in which a black woman, owner of a book shop, is randomly attacked by a young white thug. Not that black immigrants live in fear of being under constant threat: it is just that Levy relishes the wit of using innuendo and insinuation to expose racism in speech.

In Chapter Twelve, for instance, race lurks in conversations between Faith and the parents of her white boyfriend Simon, especially with a friend of Simon's parents – Winston Bunyan. Nor is such preoccupation with race all on one side: Faith's parents do their best to foster a relationship between her and Noel, a black work mate of her father's, presumably because they think she should marry black; and her brother Carl's white girl friend, Ruth, who sees race in every nook and cranny, impulsively counsels firm, militant action against "European oppression" when she hears about a job interview in which Faith fears she may have got the wrong end of the stick. Ironically, Faith does get the job despite her fears and Ruth's militancy seems misguided.

As hinted above, though, Fruit's real appeal is in Part Two with Faith's account of staying with her mother's sister Coral in Jamaica, and meeting extended family like her cousin Vincent - aunt Coral's son - and his wife and children. Although impressed by Jamaica's tropical sunshine, luxuriant growth and outdoor life, Faith is jolted by cultural differences between herself and her "fellow" Jamaicans. At the airport itself, she is reduced to tears when a man steals five dollars from her and her luggage is misplaced. Most troubling of all is Faith's awareness that these incidents are considered normal or routine, airily dismissed with a mere shrug, and that she is now part of a culture which prides itself less on organisation than on improvisation, on unexpected impulse rather than timely planning.

Most importantly, Faith realises that Jamaican society is regulated by values of race, colour and class. This is not the "simple" racial discrimination of Whites against Blacks that she knew from England. Race in Jamaica is endemic, deep-seated, fundamental, and Faith gets caught up in it. Here is her own description of Gloria, her cousin Vincent's wife: "Gloria's nose was flat and broad and her hair which was straightened, was round and curly on her head. She had very dark skin. A rich dark blue-black that had no highlights of a paler colour." Faith associates Gloria with the Black and White Minstrels show although, to her credit, she also confesses: "I was ashamed of the thought."

This bitter exploration and recognition of ancestral roots emerges most clearly in six chapters of Part Two of the novel which are narrated by her relatives, mostly by Faith's aunt Coral. Each chapter contains the fully fleshed biography of an older family member, and despite looking like individual lectures on family biography – part of a perfunctory narrative strategy already noted – these chapters collectively provide a vibrant record both of Faith's family history and challenging (bitter) local conditions that drive Jamaicans to emigrate or serve in the First World War. Bitterness is suggested by the novel's epigraph which consists of one four-line stanza from the folk song by Will Holt, comparing love to the lemon tree which may look pretty and have sweet flowers, but bears a fruit that is impossible to eat.

As wryly implied in this epigraph, and as she perceives in racial ethics that Jamaica inherited from its British colonial history of African slavery and exploitation, Faith's well-intentioned search for roots, inspired by her mother's loving advice: "Everyone should know where they come from" turns out to be at least bitter-sweet. That such tragic historical circumstances should inspire a narrative of full blooded and richly individualistic characters, superbly described scenes, pungent speech and bubbling wit is nothing short of a feat, Levy's piece de resistance being Faith's light-skinned cousin Matilda who brings up her pass-for-white daughter Constance as an anglophile who eats lemons in the English way, and is educated in England, yet marries a Rastafarian, has a son named "Kofi," travels to Africa, changes her name to "Afria," and wears African clothes - fruit of the lemon, indeed.

278 pp. Farrar, Straus & Giroux

A review by Dinaw Mengestu

In the opening paragraph of Rahul Bhattacharya's first novel, "The Sly Company of People Who Care," the unnamed narrator, a former cricket journalist from India, declares his intentions for his life, and thus his story — to be a wanderer, or in his words, "a slow ramblin' stranger." That rambling, through the forests of Guyana; the ruined streets of its capital, Georgetown; and out to the borders of Brazil and Venezuela, constitutes the novel's central action. But its heart lies in the exuberant and often arresting observations of a man plunging himself into a world full of beauty, violence and cultural strife.

It's impossible, reading Bhattacharya, not to be reminded of V. S. Naipaul, even if he weren't referred to several times throughout the story. Naipaul defined the lonely, empty middle ground occupied by the descendants of Indian immigrants living in Africa and the Caribbean who no longer belong to any nation. Bhattacharya's narrator, despite having been born and raised in India, occupies similar territory, having given up on his country and the identity that was supposed to come with it. By and large, though, the similarities end there. Unlike Naipaul's disillusioned protagonists, who stand perpetually outside the world they live in, Bhattacharya's narrator is thoroughly invested in Guyana and its striking blend of cultures, born out of colonization, slavery and indentured servitude. If anything, he is more reminiscent of Dante in the case of the "Commedia," a careful listener and observer who, while in exile, faithfully records the stories that come his way.

For Bhattacharya, that listening and recording means creating a narrative loyal to the traveler's experience, with all the awe and confusion that attend it. His novel is populated with images and people skillfully sketched rather than fully developed, so that often all that remains in the reader's mind is the small detail — the upside-down watch on a man's wrist, the plum-size dimples on a woman's face. Similarly, the creole animating the novel's dialogue and the often fleeting appearances of black and Indian characters seem to be incorporated at times less to illuminate than to add an auditory texture to the fictional world.

There is, inevitably, a disorienting quality here. Bhattacharya resists lingering too long in any one place or with any one person. As his narrator takes the reader through his apartment building in Georgetown and his impressions of its people ("Hassa the dead-eyed minibus driver; a pair of busty Indian-Chinese cashiers who people called Curry-Chowmein"), he reveals almost nothing of himself. The novel's seduction, and the reason it deserves close reading and admiration, stems from its expansiveness and the quick movements of its prose, which can leap nimbly from a casual conversation with a con man to a trip into the jungle with that same con man in a single page.

The novel, thankfully, resists offering easy characterization of a culture that has to be seen and heard before it can be understood, of a place "ripe with heat and rain and Guyanese sound and Guyanese light in which the world seemed saturated or bleached, either way exposed."

The narrator's first expedition into the interior of Guyana to go diamond hunting, or "porknocking," comes about as a matter of chance. He's driven by whimsy but retains his depth of vision. Bhattacharya avoids the usual pitfalls of writing about a foreign culture with the intention of discovering something about it — a goal that all too often finds writers resorting to sweeping generalizations. The narrator describes the "slow-watching" of a waterfall and stands "alive in the drizzle, filthy-footed." There is a music behind everything: in nature, the "amphitheater of leaves"; in life, the rhythms of the local language, and of the reggae whose lyrics of protest are constantly evoked.

In a village of porknockers, a half-dozen people (with names like Dr. Red and Nasty) share the page as they drink, argue and fight. They and other characters — including my favorite, Ramotar Seven Curry, known for his devotion to attending weddings — come to life in all their eccentricity, their humanity and flaws intact.

Bhattacharya's narrator emerges from his adventures seeking answers about Guyana's past, and the country's history — from the arrival of the first European explorers and the African slaves they brought with them, to the importation of impoverished Indian workers, or "coolies," as indentured servants — is gracefully retold. Bhattacharya uses the complicated webs of African, Portuguese and East Indian identity flowing through Guyana to reveal not only how the country was settled, but also how differences in race and class came to breed bitter discord. Guyana is consumed by race, and the author's subtle and repeated shredding of seemingly indelible racial divisions is one of the novel's great achievements. Here he describes the "putagee," or people "of Portuguese extraction": "Portuguese had come to Guyana as indentured laborers even before the Indians and the Chinese. They were light-skinned and independent-minded. They rose up the ranks, and now, small in number and of high position, they could look at race as something they were not a part of." And on the people of a coastal settlement: "The folk at Menzies Landing were black, or more often red. . . . In the direct Guyanese way a red person was a direct visual thing. It implied mixed blood and, obviously, a certain redness of skin. Black and Portuguese could be red. Black and Amerindian could be red. East Indian and Portuguese could be red."

One wishes at times that Bhattacharya had tried to include less in order to say more. A second layer of description following the narrator's move to a new house occupies too much space in an already crowded novel; a journey to the Brazilian border takes too long. By the time the narrator is finally drawn to a single character, a gorgeous young woman of mixed race (mostly "cooliegal," though "my father got a lil Brazzo in him," she says), both their romance and their travels together feel artificial, in part because the narrator remains more a guide than a character, one who points the reader's attention to the hidden corners of a society while keeping the secrets of his own heart at bay. He may occasionally try the reader's patience, but that's only because he wants you to see what a remarkable and exquisite world he has made.

(Courtesy: The New York Times)