Book Review

Poems, Hong Kong, Proverse Hong Kong, 2011, pp.176.

ISBN – 13:9789881932136

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

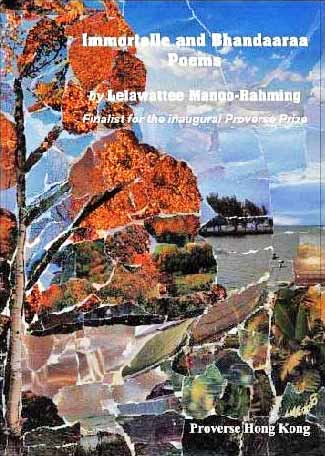

Immortelle and Bhandaaraa Poems, Lelawattee Manoo-Rahming's second collection of poems, comes eleven years after her trail-blazing first volume Curry Favour which signalled her arrival as a leading Caribbean poet. Versatility is evident in her qualifications as a Mechanical Building Services Engineeer, in her works of sculpture, drawing and painting, and as if to demonstrate this point about versatility, mixture or diversity, Manoo-Rahming - an Indo-Trinidadian - is married to a Bahamian, lives in the Bahamas, and includes nine of her paintings in Immortelle, each associated with a particular poem in the volume. Immortelle was also a finalist in an inaugural poetry prize organised by the Proverse group –the volume's publishers.

Mere titles of the five sections into which Immortelle is divided announce the pan-Caribbean, not to say global/universal scope of its themes. For example, Hindu goddesses Bhavani, Durga, and Shakti in the titles of Sections One, Two and Five respectively, Coatrische an indigenous Caribbean goddess in section Three, and the classical Greek goddess Hecate, Queen of Night, in Section four, all point to the poet's devotional approach and reliance on the influence of divine intervention in human affairs. Manoo-Rahming's devotion to divine beings who are female also betrays distinctly feminist concerns although, as hinted in the title to the volume's fifth section describing the goddess Shakti who "Surrrounds and Animates the Energy of the Male God," feminist concerns are generally presented within a larger, more all-embracing framework of equality irrespective of gender.

Like titles of her five sections, Manoo-Rahming's title for all her poems speaks volumes, for it defines two focal points of her inspiration: the immortelle which was planted as a shade tree on cocoa plantations in Trinidad and Tobago in colonial times, thus proclaiming the Caribbean as the physical location of her subjects, and "bhandaaraa" which identifies the Hindu metaphysical structure of many poems in Immortelle. As "Immortelle" grounds the volume's poems in a solidly documented Caribbean history of cultural deracination and political and economic victimisation, "Bhandaaraa" - a Hindu ritual that assists the soul to achieve release from the body of a dead person - provides a coherent theology for discussing basic limitations of human finiteness.

Awareness of finiteness - a persistent gap between human aspiration and achievement – inspires some of Manoo-Rahming's best poems: those driven by an elegiac sense of loss upon the death of close relatives or friends to lament the mortal curse that subjects our deepest strivings and aspirations, for example, those of family loyalty, solidity and love, to inescapable processes of change, decay and dissolution. Her lament which derives from a natural instinct to probe the mystery of death appears in devotional writing by many English poets from George Herbert to John Donne, William Blake, Christina Rosetti and Gerard Manley Hopkins. Yet there is nothing borrowed or derivative in the authentic Caribbean context or the profoundly creole (mixed) Hindu, pantheist, even Christian reflections of Manoo-Rahming's poems.

In "Deya for Ajee," the first poem in Immortelle, the persona pleads with her dead paternal grandmother, her Ajee, for wisdom: "To see in you my goddess Durga [one who can redeem situations of utmost distress] / Helping me to battle the demons of this life." While death causes pain from loss and grief, life is no picnic either. True safety or security must be sought from insights, through metaphysics, in a sphere beyond life. In her second poem "Mirror Glimpses" in memory of her dead mother and sister Sally, the inevitability of grief is again acknowledged when the persona detects, in a simple incident of a scorpion being found in a bag of cookies, evidence of predestination: "I took it as a sign / Sally will die." By repeating the name "Sally" in the last line of each of the poem's four stanzas, the crashing finality of the last line of the fourth stanza: "Sally is gone." packs a punch of such eerie, supernatural power that it leaves no doubt at all about the abject inadequacy and fragile impermanence of our lives. Then "Washerwoman" celebrates Sally's resolve to overcome the harshness of her life as an impoverished single parent with a glorious burst of alliteration and onomatopoeia, when it compares Sally's sorry life and death to mere sounds of someone handwashing clothes: "Just your spirit escaping squooshhhhh / Like air in the squish, squish, squish." That the supreme sacrifice of Sally's lowly life is worth no more than sounds of washing dirt away is no different from the bitter comment of the brutally blinded Gloucester who wryly concludes in King Lear that human life has no more significance than that of: "flies to wanton boys."

Other poems illustrate Manoo-Rahming's boldness and inventiveness in employing a variety of subjects and techniques. Some poems celebrate the lives of artists, musicians and murder victims while others combine episodes from history with contemporary Caribbean scenes and incidents. In the process, literary and cultural references are boldly drawn from places as distant as Ireland, Malaysia, and Polynesia, while explicitly erotic poems like "My Coontie" and "Ghazal on Ageing" reflect equal fearlessness in confronting sexual attitudes hidebound by prudish or sterile convention.

What stands out in Immortelle is a deeply ingrained creole instinct, Trinidadian in flavour, for mixing and innovation. It is not just Manoo-Rahming's prodigal wordplay and coinages, for example, "MuchworsethanGodforlife," or "ovadotcom" and "planesforpeople," nor her comparison in "Immortelle" between Trinidad's Piparo forest and the fabled forest of Rama's banishment in the The Ramayana. Technically, it is her expertise with multiple devices: lines of different length in the same poem, varying numbers of lines in different stanzas of a single poem, the repetition of words or phrases as a structural device in many poems, and brilliantly original images sometimes extended effortlessly over several lines. Most of all, though, it is her uniquely creole voice used to express universal insights that clinches Lelawattee Manoo-Rahming's position as one of the leading poets in the Caribbean today.